Hong Kong’s protest art helps fuel valiant fight to save its freedoms

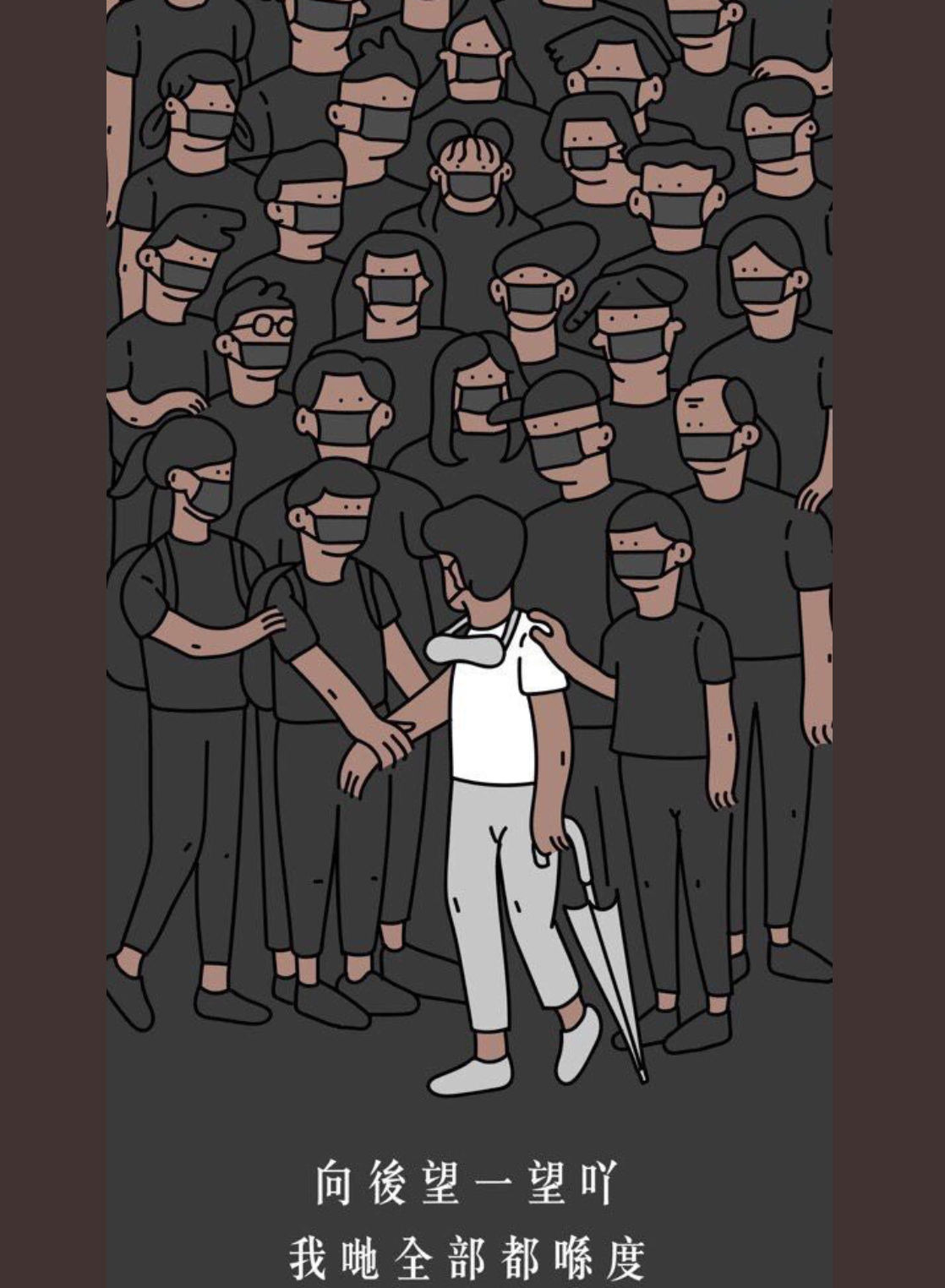

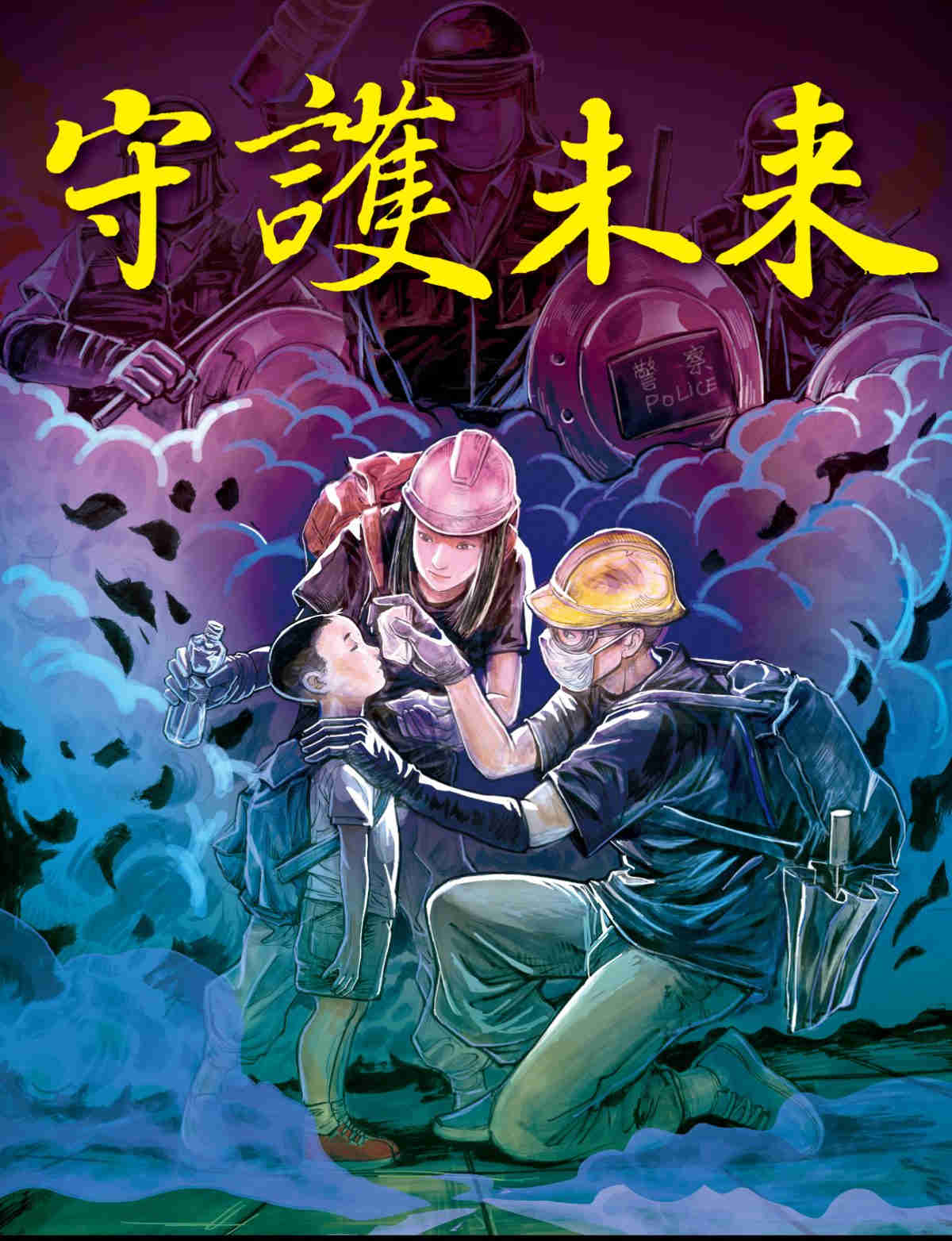

'Hong Kong Withstands' by artist Daxiong

All summer long now, millions of Hong Kongers have been pouring on to their city’s teeming streets—to march in the blast-furnace heat or trek beneath torrential tropical rains. Their single gallant goal: to force the world’s most powerful police state to keep its promise to them.

In 1997, when Britain returned Hong Kong to China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) promised Hong Kong’s people that this illustrious financial centre on the South China Sea would be ruled as a “Special Administrative Region” as “one country, two systems.”

China vowed that for another 50 years Hong Kongers would maintain all the rights and liberties that they enjoyed under British colonial rule—including the rule of law, freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, privileges never permitted on the Mainland.

However, since 2014 the CCP has been relentlessly breaking its promise, “suggesting” a cascade of far-reaching changes to the city’s social, educational and legal life. The final straw came in June, when the HK Government tried to introduce an Extradition Law that would allow any Hong Konger to be extradited to China, thus subject to Chinese Communist Party law. Average annual criminal conviction rates in China? Just north of 96%.

The first few protests were entirely peaceful. But as the HK Government ignored them, the marches became ever larger, growing into the millions, and violent breakouts began. Police, now decked out in combat gear, started to use tear gas and batons on now impatient, unruly crowds. College students were joined by their parents. Civil servants and doctors, airline staff and school teachers marched. 3,000 members of the century-old Hong Kong Law Society marched—twice. Then 9,000 elders (“Silver Citizens”), marched in the sizzling heat, including one elderly gent I saw lurching along, on crutches. With one leg.

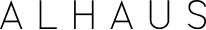

Protest art reading ‘We leave together’

As might be expected of such an uber-modern metropolis, social media is being used by the protesters to instantly plot and plan their every move. But also fuelling this city’s valiant fight to save its freedoms is a virtual explosion of unique protest art.

Some of the most biting posters have been produced by a mainland-China born artist now based in Australia, who goes by the name of Badiucao; he has allowed his work to be freely reprinted to spread Hong Kong’s story. But hundreds of other young professional graphic artists and ad agency art directors—and even thousands of amateur artists—are adding their graphic skills to T-shirts and Twitter and Facebook memes (as well as on hundreds of so-called “Lennon Walls”) all across the city. Many new posters appear literally overnight, creatively communicating something that happened yesterday or an event planned for tomorrow.

“While the weeks have whizzed by, Hong Kong’s now-historic protest pop art has evolved with the protests themselves.”

While some artworks, or ever rude pen and ink sketches, have English words, most use Chinese calligraphy, meaning that even the characters themselves can be designed to be powerfully emotional, a mocking style aimed at some bumbling government bureaucrat, or another style appearing to drip blood to honour a brutally injured protester.

And while the weeks have whizzed by, Hong Kong’s now-historic protest pop art has evolved with the protests themselves. Initially protesters hoped that the government would understand the justice of their cause, and their artwork reflected this fleeting feeling with shy wit—protester posters showing marchers feeling safe in singlets , shorts and flip-flops, as if heading to a beach BBQ.

Satirical image from early days of Hong Kong protests

“Currently, most of Hong Kong’s millions of young pro-democracy demonstrators—including many tens of thousands of optimistic teenagers—remain peaceful. This, despite police brutality being relentlessly increased.”

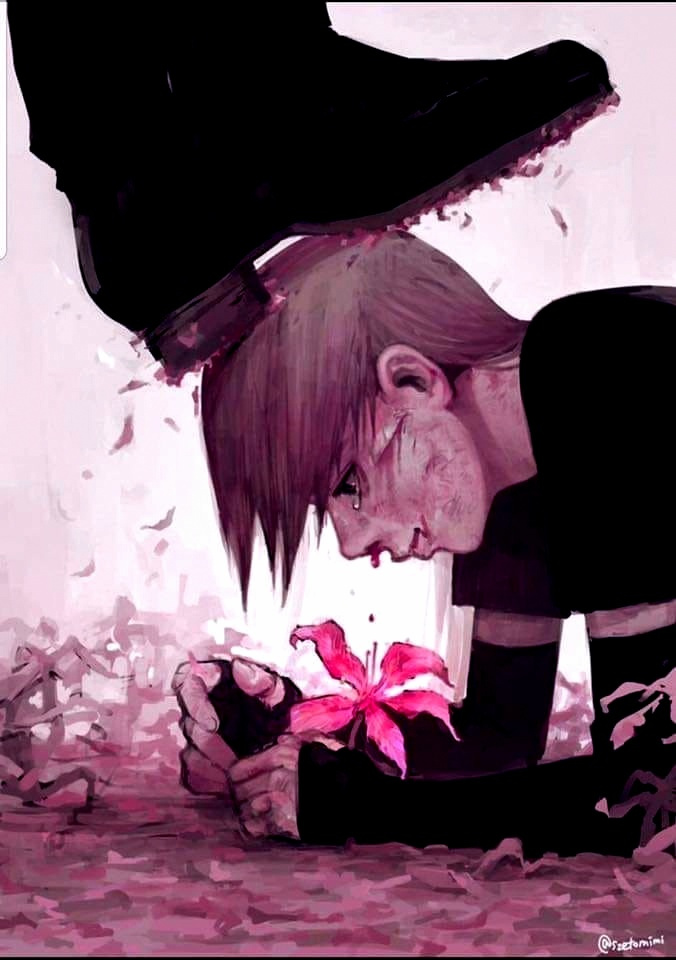

But as the police became ever harsher in dealing with the freedom fighters, the protest art itself became steadily darker—with marchers now shown wearing helmets, goggles and gas masks as a defence against truncheons, and tear gas and water cannons.

Currently, most of Hong Kong’s millions of young pro-democracy demonstrators—including many tens of thousands of optimistic teenagers—remain peaceful. This, despite police brutality being relentlessly increased.

Just 48 hours ago, a young man noticed a gaggle of police searching for something on the street. He shouted: “Are you searching for something? Are you searching for your conscience?” The baton-wielding police chased him down before beating him almost senseless, then walked away. All of it captured on video.

So, by now it would not be surprising if the exhausted and anguished citizens of Hong Kong begin to align their thoughts with those of Daniel O'Connell, regarding another battle for human rights, long ago and far away from the teeming streets of this beautiful Asian city—that simply wants to remain a free society.

O'Connell said: “Whatever little we have gained, we have gained by agitation, while we have uniformly lost by moderation.”