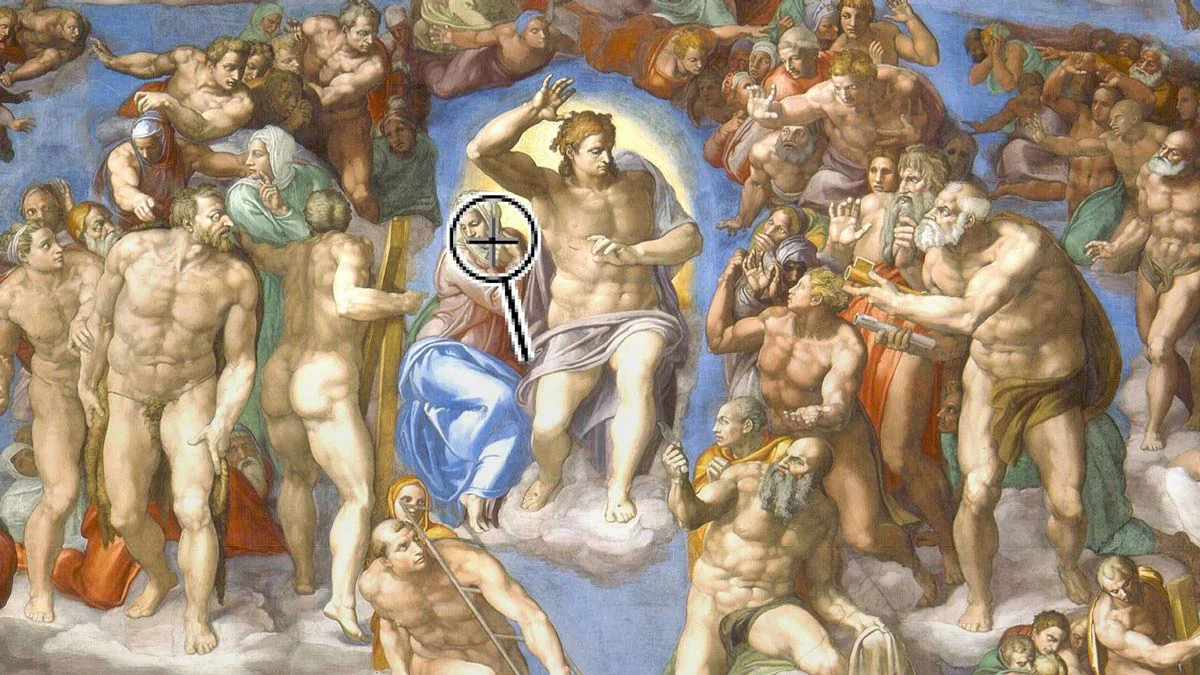

The Sistine Chapel on my desktop

Sinéad McClure explores the dissemination of the visual arts through online curation.

The first time I visited the Musée d'Orsay, I was absolutely transfixed by how realistic everything appeared. It wasn't just the artwork, or the style of what was on display; it was being able to move silently along the tiled floors. It was the polished marble plinths and the wide-open passageways, cement pillars bearing their weight. It was Paris—granted, without the café noir and croissant accompaniment—and I was there. I still have that CD: ‘Musée d'Orsay: Virtual Visit’ for Mac/Win 3.1/95. Windows '95 was the vehicle for my virtual journey. The museum houses one of the finest collections of French Impressionism, and to be able to visit it from the comfort of my newly purchased office chair was invigorating.

Recently I had reason to revisit the Musée d'Orsay, and this time my vehicle was the internet; specifically Google Arts & Culture. This is a partnership between Google and some of the world's most famous museums and art houses. Showing work from over 250 institutions and pieces by 6,000 artists, it's a collection of epic proportions. You could spend hours touring through each wonderful gallery, thanks to the same technology that powers Google Street View. There are over 45,000 artworks available to view in high resolution; this is a living collection, growing constantly.

Online arts curation is one of the true joys of the internet. From podcasting music and showcasing literary works to viewing paintings, sculptures and contemporary arts; from sharing techniques to introducing new artists, and beyond. It's also contagious: artists and curators like to share. There are Instagram accounts that bring us every drop of colour we crave, and have a picture for every quote that aspires to inspire our day.

This is a wonderful time to look, listen, submerge yourself in and be inspired by creativity. Curating arts, databasing, and sharing the methods of the masters is part of why the internet was created. I can go into a national library online and find a photograph taken in the early part of the 20th century, or explore a museum collection preserved and itemised for research. I can study Van Gogh's Sunflowers in high resolution or virtually visit the Van Gogh Museum in the Netherlands and see it hanging on the wall. The resources that are available at the click of a mouse or the touch of a finger seem limitless.

I have found a virtual tour of the Sistine Chapel—I hit the wrong mouse button and swing the 360° camera down to the floor. There, I'm met with something Michelangelo didn't paint—‘Copyright MV–Musei Vaticani’—and am reminded for a second of the importance of proprietorship, before I swing the view back up towards the ceiling. This took four years to paint and is over 500 years old. I'm temporarily gobsmacked, and dissuaded enough by the trademarked floor to resist the temptation to hit ‘print screen’ and capture a new wallpaper for my desktop. After all, a return visit is only a click away.